Home > Georgia > Georgia Technology > Modern Technology Pushes Poultry Industry Into Future

Modern Technology Pushes Poultry Industry Into Future

Edrie Campbell started raising chickens for market on her Jefferson, Ga. land in the mid-1940s, creating a business that now extends to the fourth generation of her family and provides a glimpse into how the poultry industry has helped position Georgia as one of the top agricultural states in the nation and first in poultry production.

Poultry is Georgia’s largest agricultural segment, accounting for 47 percent of the state’s farm gate value. On an average day, Georgia produces 29 million pounds of chicken; poultry contributes an estimated $18.4 billion to the annual economy and generates 100,000 jobs.

But in the 1940s, growing chickens to market was just beginning. World War II created a demand for food, and innovative in people in north Georgia like Edrie Campbell entered the business.

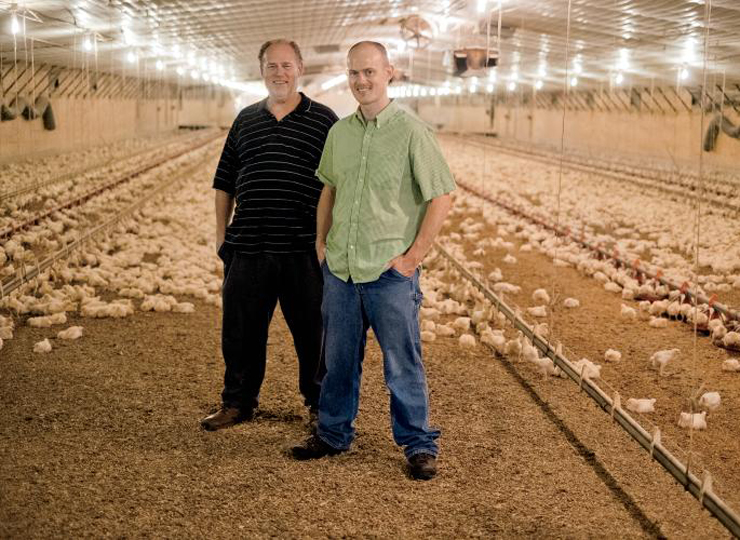

“It was a lot different then,” says Brandon Boone, Edrie’s great-grandson. He and his father, John, share responsibilities for the operation of Boone Farms on that same land. “She, and then my grandfather, had three little houses, maybe 5,000 to 10,000 birds and nothing electric, just a manual operation. My dad and I run a three-house operation, too, but we have 112,000 birds and each house is fully computerized and environmentally controlled.”

The ability to control the temperature in the houses is a key advancement in the poultry industry. Not that many years ago a serious heat wave would have caused significant losses, and Brandon remembers hearing his grandfather’s stories of building a fire in the poultry houses to keep the new chicks warm enough during extreme winter temperatures. Thanks to research at the University of Georgia, tunnel ventilation and cooling cells changed the nature of the industry and highlighted the importance of the partnership between the state’s university system and its agricultural industry.

“We can maintain temperature within a degree or two from the front to the back of the houses,” Brandon says, noting he and his father can monitor temperature changes through applications on their cell phones and make adjustments remotely when necessary. Even on Georgia’s hottest summer days, the combination of evaporative cooling and wind chill in modern tunnel-ventilated broiler houses keeps the temperature the chickens feel in the mid 70s.

“The bottom line is that the birds need to eat and grow,” Brandon says. “The nutritional research at the University of Georgia is helping us achieve that goal with less feed in less time. Where it used to take my great-grandmother up to 12 weeks to get birds to market weight, we’re getting there in about half the time.”

Boone Farms is part of Georgia’s successful vertical integration farming program. The Boones own the land and houses and contract with poultry processors to provide the chickens, which are then marketed to restaurants, grocery stores and food-service providers.

The success of Boone Farms mirrors the success of many of Georgia’s family farms, says Abit Massey, former president of the Georgia Poultry Federation and one of the state’s leading experts on the history of the industry in Georgia.

“We’ve seen a lot of growth over the years,” Massey says. By 1960, Georgia was producing about 300,000 broilers, a number that is up to 1.4 billion annually today.

He credits the state’s university system, including UGA and Georgia Tech, with advancements in the industry as well as historically strong support from the Georgia legislature. At the same time, poultry companies have achieved significant innovations over the years that have made the industry more efficient and productive, while providing a safer product for consumers.

Massey says the industry’s growth is also tied to its success in developing new products, thus increasing the appetite for poultry. In the early 1960s, whole chickens accounted for 90 percent of the birds sold to consumers. With more than 3,000 chicken products available in grocery stores today, whole birds account for about 10 percent of sales.

What was once a north Georgia industry has now spread throughout the state, with more than 105 counties producing more than $1 million in poultry at the farm level.

“It’s no stretch to say that Georgia is a world leader in the poultry industry,” Massey says, noting that if Georgia was a country it would rank seventh in poultry production. People from all over the world recognize Georgia’s leadership in the industry. The state hosts the annual International Poultry Expo, which is the world’s largest display of technology, equipment supplies and services used in the production and processing of poultry and eggs and manufacturing feed.

Poultry is serious business in Georgia, but Massey says there is room for a chuckle about the state’s love for chicken. In Gainesville, Ga., which has laid claim to the title Chicken Capital of the World, a statue of a rooster serves as a monument to the industry, and the city hosts an annual Chicken Festival that serves 4,000 pounds of the deep-fried delicacy. If you go to the festival or eat at any restaurant in the city, Massey says beware of what he describes as a “tongue-in-beak” law making it illegal to eat fried chicken in any way other than with fingers. No forks allowed.