Home > Illinois > Illinois Crops & Livestock > Illinois Ranks Among Top States for Ethanol Production

Illinois Ranks Among Top States for Ethanol Production

If corn is king in Illinois, then ethanol is definitely prince. A decade ago, 55 percent of the country’s gasoline supply came from imported oil; today, that number is 45 percent. And ethanol is the big reason why. In addition, ethanol now accounts for one out of every four gallons of fuel produced from domestic energy sources.

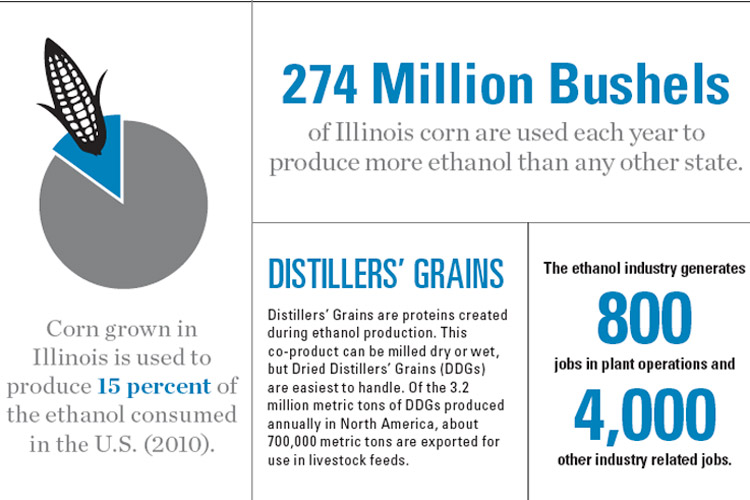

In Illinois, that growth means good business. With 14 ethanol plants in the state producing 1.7 billion gallons of ethanol each year, the industry utilizes 670 million bushels of Illinois corn, employs nearly 4,000 workers, and adds about $5.3 billion to the state’s economy. It’s an industry that fuels much more than gas-powered vehicles.

“Ethanol has been the economic engine of agriculture throughout the United States,” says John Caupert, director of the National Corn-to-Ethanol Research Center (NCERC). Illinois is a good example, he explains, because “it’s an industry that has provided tremendous financial stimulus for rural areas, which, in turn, has been good for business across the state.”

In fact, Illinois’ strong reputation as corn country and its role as one of the pioneers in ethanol production have made it not only a prime location for the industry but home to the NCERC as well. Located on the campus of Southern Illinois University in Edwardsville, the center is a non-profit research facility that works with clients to facilitate the commercialization of their biofuel product or technology. Most clients are vendors to the biofuels industry, which includes conventional ethanol, cellulosic ethanol, advanced biofuels and other specialty chemicals. Private sector clients utilize the NCERC pilot plant for demonstration testing of their products and technologies.

“Our pilot plant has every single process unit that a typical corn ethanol plant has,” Caupert says. “We’ve just shrunk it from a volume perspective. If it happens in a commercial ethanol plant, we can do it here.”

That allows clients to test their technology and show their customers or investors real data from a real facility. At the same time, it protects their intellectual property, since the center’s clients are fee-for-service and own all the data produced from their project.

The Perfect Blend

What is responsible for the growth of the ethanol industry? Much of it can be attributed to the Renewable Fuels Standard (RFS), which was passed in 2005. RFS calls for the United States to increase its consumption of renewable fuels each year. In the first year, 2008, the goal was a minimum of 9 billion gallons. Corn farmers across Illinois and the country took up the challenge, meeting production expectations even as the targets rose each year. But that success raises new challenges.

Now, as production reaches the ceiling established by the RFS and consumers use less fuel by driving fewer miles and buying fuel-efficient vehicles, less ethanol will make its way to the marketplace. “The way to overcome that is to have higher blends of ethanol and gasoline,” Caupert says, suggesting that moving from the current 10 percent blend to a 15 percent blend would be a win-win for the industry and the environmentally conscious consumer.

Protein-Packed Profits

Renewable fuel isn’t the only valuable commodity produced at Illinois ethanol facilities. The production of ethanol creates proteins called Distillers’ Grains, a co-product that can be milled dry or wet. Dried Distillers’ Grains (DDGs) are the easiest to handle, and most ethanol plants dry their Distillers’ Grains. Exporting DDGs provide additional opportunities for producers. Marcus Throneburg, director of DDG marketing for Marquis Grain in Hennepin, says that on average ethanol represents 80 percent of revenue for the plants and DDGs are responsible for 17 percent of the revenue, with other byproducts, such as corn oil, responsible for the remaining 3 percent.

Throneburg says DDGs serve primarily a replacement for corn in livestock feed, making up between 40 and 50 percent of the beef cattle’s diet and 30 percent of the swine’s. Nearly 80 percent of DDGs are used by American livestock producers, and 20 percent are exported, with Mexico, China, Canada and Vietnam being the largest buyers.

“If you’re exporting the product, it has to be dry for shipping,” Throneburg says. “And because we are located near Chicago for grain movement and close to the river for export through New Orleans, we dry all of our DDG. Other states whose geography isn’t as conducive to exporting will produce wet distiller’s and distribute domestically.”

Throneburg says that when ethanol plants began production, naysayers felt that DDGs would not be a profitable byproduct – that there would be too much of it and that the excess would have to be disposed of. But those predictions have not panned out, nor have the predictions of those who thought the production of ethanol and its byproducts would compete with food production.

“Statistics indicate we are producing 47 percent more corn today than we were on the same number of acres a decade ago,” Caupert says. “We’re not only satisfying all market demand, but foreign demand is at historically high levels. If American farmers are allowed to do what they do best, which is produce, there will never be a food versus fuel issue.”